A new method for studying the sport

By Josh Woods ~

I’m not a fan of phrases like “close, but no cigar” and “close only counts in horseshoes.”

They make it sound like close is a bad thing. As if anything short of first place, anything other than perfection, anything besides certainty is a grave defeat.

Even Reese Bobby’s celebrated absurdity – “If you ain’t first, you’re last” – was debunked by Reese himself at the end of Talladega Nights.

Black-and-white thinking doesn’t work well as a sports mentality, and it’s even worse for science. Scientific research never leads us out of the grey, not entirely. At best, we merely increase our confidence in fundamentally questionable propositions.

As discussed in a previous post, I’ve been researching disc golf for more than two years and I just landed my first academic publication. Yep, science is grey and slow.

In this post, I’m going to review the method I used to answer three basic questions about the sport:

- How many people play disc golf?

- What does the disc golfer population look like?

- What motivates participation?

At first, I thought this would be easy. I was wrong. Part of the challenge of studying disc golf lies in the lack of previous research. When earlier scholars pave the way, it’s easier to push new research forward.

But that’s not the only problem. Disc golfers are just hard to study. The community is relatively small and thinly spread across the world. We have some great data on PDGA members, but non-PDGA players are elusive creatures indeed.

I’ll start by reviewing how other people have studied disc golf, and then give you the skinny on how I did it.

Unverifiable Estimates

A lack of scientific knowledge has not stopped people from making big claims about the sport. For instance, a chorus of voices has christened disc golf as the “fastest growing sport in America.”

While there is evidence of growth, the difficulty of determining whether disc golf’s rate exceeds that of all other sports cannot be overstated. In fact, whenever you see the phrase “fastest growing” attributed to any sport, you can be sure the statement is profoundly empty.

More interesting is speculation offered by well-known disc golf authorities. Each year, the PDGA publishes demographic reports on its active members, events and known courses. Many of these reports also include a general population estimate.

For instance, a PDGA report released in 2017 included this statement: “An estimated 8 – 12 million players have played disc golf; two million are estimated to be regular players.”

While such estimates are interesting, and may be valid, there is no way to evaluate them unless we know how they were constructed. How was the category “regular player” defined, and what mechanism was used to put two million people in it?

The Black Box

There are several potentially interesting sources of data on disc golfers. If, for instance, the top disc manufacturers released their sales figures for the last ten years, we could construct an intriguing estimate of the number of players, or at least determine the sport’s rate of growth based on disc sales.

Yet, as discussed previously, the major disc manufacturers are not keen on sharing this information.

Survey-Based Estimates

For many social scientists, surveys are the bread and butter of demographic analysis. Unfortunately, even if you can afford this pricey option, it might not work.

Given the relatively small number of U.S. disc golfers, a typical, large-scale survey of the U.S. population would return such a tiny number of regular players that statistically accurate, demographic analyses would be impossible (1).

Another strategy involves targeting the disc golf community itself. For instance, when Steve Dodge worked at Vibram, he collected data on the PDGA membership status of Vibram’s online disc golf customers.

During an email discussion with Parked back in 2016, he wrote: “In 2003, our online disc golf store and a friendly online store calculated that about 2% of our sales came from PDGA members. Since then, it appears that this number has gone down, perhaps to 1%.”

It’s tempting to assume that Vibram’s online customers were representative of the general population of disc golfers. If such an assumption held up, we could compute a valid estimate.

Here’s how it would work: The PDGA reported that it had 8,304 members in 2003. If, as the Vibram sample suggests, only 2% of disc golfers had a PDGA membership, we could estimate, using ninth-grade algebra, that 432,503 people played disc golf in 2003.

Computing the same figures for 2015 (the PDGA reported 30,454 members in 2015, and Vibram estimated the PDGA-membership share at 1%), we could further conclude that the total number of disc golfers was 3,075,854 in 2016.

But here’s the rub … actually, there are three rubs.

First, the representativeness of Vibram’s customers is unknown. It’s possible that many people who purchase discs online are not regular players. It’s also possible that some PDGA members simply forgot or decided not to respond to Vibram’s query for their PDGA status.

Second, there is no way for outside researchers to verify the Vibram study. This is not to say that Dodge’s claims are suspect. The point, rather, is that science requires replicability. And there’s no way for anyone to replicate the Vibram study, or any research based on proprietary data.

Third, applying this same approach to other available data sources leads to vastly different estimates.

For example, the State of Disc Golf Survey is the most extensive, longitudinal study of the sport. The survey carried out in 2014 found that 33 percent of respondents were PDGA members. One year later, in 2015, the share of PDGA members rose to 50 percent. This means that the number of non-PDGA members declined over this period, which is … well, not good.

The State of Disc Golf survey suggests that the total number of active disc golfers in the U.S. dropped from 98,513 in 2014 to 91,362 in 2015.

Of course, the population probably did not decline. It’s far more likely that the sample simply became more PDGA-centric over time. People who are highly committed to the sport are probably more willing to fill out a disc golf survey, year after year, than people who are less committed. And it’s safe to say that committed players are more likely to join the PDGA than casual ones.

Here’s the takeaway: The representativeness of a sample depends on how the sample is collected. If you want to use a sample to say something about a population, the size of the sample matters far less than the sampling procedure.

When disc golf surveys are spread via social media and respondents are collected through opt-ins or self-selection, the results will be biased by the variable willingness of people to participate. This type of survey is interesting and important but should not be used for estimating population parameters.

A New Method

A better strategy is to create a giant list of disc golfers, randomly select a sample from it, and then use the findings from the sample to infer things about the giant list. So, where can we find such a list?

Many researchers have responded to the challenges of studying low-prevalence, hidden, or hard-to-reach populations by utilizing social media sites for data collection (2). Social media can provide an extensive sampling frame (giant list) of people that approximates a given population. Facebook may be one of the only feasible tools for establishing a reasonably large sampling frame of disc golfers.

In recent years, Facebook users have become more representative of the population. In 2015, 72 percent of adults on the internet had a Facebook account (3). Among Facebook users, roughly three out of four access their accounts daily (4). Women (83 percent) are only slightly more likely to use Facebook than men (75 percent). While younger Americans are more active than older people, the rate of use is similar among a large age cohort (ages 18-49), and variance across income and education levels is small (5).

Differences in Facebook use across racial-ethnic background and region are also minor (6). Facebook includes users who are more representative of the U.S. population than any other social media platform (6).

For more than a year, I’ve been working with two students on a disc golf study based on Facebook profiles. In my next post, I’ll post the findings of the study. In this post, I’ll offer a detailed description of our method. A full draft of the report will be available in the International Journal of Sport Communication early next year.

The Parked Facebook Study

To construct a sampling frame, we began by searching Facebook for disc golf groups. At the time of the initial data collection in late 2016, searches using multiple terms simultaneously were deemed unreliable. Given that the sport has multiple monikers, we tested three different search terms. The dominant label “disc golf” returned 2,612 U.S.-based groups. The term “Frisbee golf” returned a similar set of Facebook groups as the disc golf search.

However, the term “frolf” (an alternative name that combines the words Frisbee and golf) returned far fewer groups. Among the 601 frolf groups, only twelve of them contained the term “disc golf” in the title. For this reason, we used a random numbers generator to select an equivalent proportion of groups (3.8 percent) from the two populations (100 of the 2,612 disc golf groups, and 23 of the 601 frolf groups).

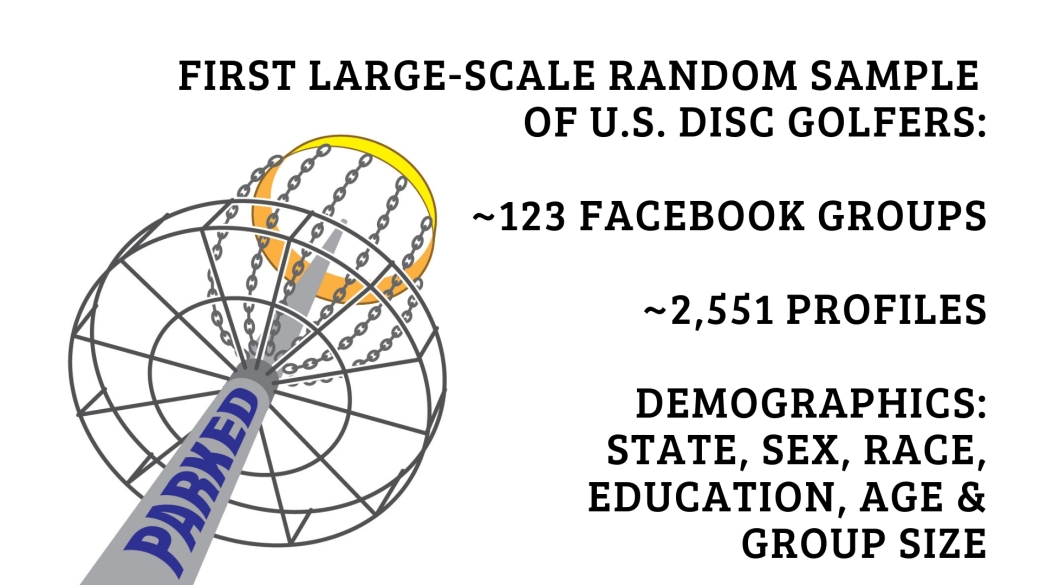

This resulted in a total random sample of 123 groups. There was not a single case of overlap between the two samples. Groups based outside the U.S. were excluded from the sample. Groups intended for the sale or exchange of disc golf equipment were also excluded.

Next, 30 individual profiles from each of the 123 groups were selected using a random procedure. If the group comprised fewer than 30 members, all members of the group were selected. This resulted in a total sample of 2,551 individual Facebook profiles. Redundant profiles were excluded. The sampling procedure was completed in April/May 2017.

This sample can be considered “random,” because each of the Facebook groups in the population had an equal probability of being chosen. Likewise, the sampling units within each group were selected through a random process. This kind of multi-stage cluster sampling approach is justified when a complete sampling frame is unavailable (7).

For each profile, we attempted to collect the following demographic data: state of residence, sex, racial/ethnic characteristics, education, date of birth, and size of Facebook group.

Caution should be used when drawing assumptions about a person’s race and sex based on photographs. Although coding these variables based on visual assessment is a common practice among communication researchers (8), the results should be understood as perceived race and sex, as opposed to self-described measures.

Still, these two indicators were shown to be reliable via intercoder testing. Two coders examined thirty profiles and agreed in all cases using dichotomous codes (white / racial minority; male / female).

To estimate the disc golfer population, each name in the sample was crosschecked with the publicly available PDGA directory, which gives the PDGA membership status of each player and his or her official rating.

PDGA player ratings are based on a proprietary formula that measures average player performances in PDGA-sanctioned tournaments and league events. Akin to a batting average in baseball, a PDGA player rating is an accepted performance measure within the disc golf community.

Finally, as a preliminary attempt to gauge the individual’s level of online disc golf activity, we coded seven behavioral markers in each profile: past or present PDGA membership (Y/N), disc-golf related profile picture (Y/N), disc-golf related cover picture (Y/N), at least one of the first ten timeline entries is disc-golf related (Y/N), at least one of the first ten page likes is disc-golf related (Y/N), member of two or more disc-golf related groups (Y/N), and proportion of total groups that are disc-golf related.

These seven indicators were combined in an index. The “disc golf activity index” is an exploratory measure. While it may be reasonable to weight some indicators differently in a future study, particularly PDGA membership, this preliminary study used an equal-weights approach. For this reason, the index ranged from 0 to 7.

Based on a subsample of subjects who had PDGA ratings, the validity of the index will be assessed by examining the correlation between the disc golf activity index and PDGA ratings. As discussed, a PDGA rating is a direct measure of disc golf behavior. If people’s online disc golf activity is a valid measure of their involvement in the sport, there should be a positive correlation between the index scores and the ratings.

Conclusion

The study described above is designed to produce demographic information about members of organized disc golf groups. It may not win a cigar on its own, but it will provide baseline estimates of the size and characteristics of the disc golfer population.

Using the disc golf activity index, we can also look at how people’s level of involvement in disc golf varies across demographic groups. For instance, previous studies suggest that people of color are underrepresented in the disc golfer population. But among those who do play, is the level of involvement in the sport greater, lesser or about the same as whites?

In other words, this study will not only estimate the proportions of various demographic groups based on state of residence, sex, racial/ethnic characteristics, education, date of birth, and size of Facebook group, but also show how these variables predict players’ level in involvement in the sport.

Ultimately, the goal is to get a little closer to understanding who plays disc golf, how many people play, and why people play.

~~~

If you’d like to support disc golf research, like Parked on Facebook or subscribe to our newsletter by entering your email address below. It really helps.

~~~

Parked is underwritten in part by a grant from the Professional Disc Golf Association.

~~~

References

(1) Kalton, 2014. (2) Bhutta, 2012; Genoe et al., 2016; King, O’Rourke, & DeLongis, 2014; Rife et al., 2016; Schneider, Burke-Garcia, & Thomas, 2015. (3) Duggan, 2015. (4) Smith & Anderson, 2018. (5) Greenwood, Perrin, & Duggan, 2016. (6) Krogstad, 2015. (7) Babbie, 1999. (8) Bruce, 2004.

* Cover photo by Jesse Wright.

3 thoughts on “What We Know and Don’t Know about Disc Golf”